Presbyopia is the normal loss of near focusing ability that occurs with age. Most people begin to notice the effects of presbyopia sometime after age 40, when they start having trouble seeing small print clearly — including text messages on their phone.

Presbyopia is on the rise in the United States as the population continues to age. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, approximately 112 million Americans were presbyopic in 2006. This number is expected to increase to 123 million by the year 2020.

Worldwide, an estimated 1.3 billion people had presbyopia in 2011. This number is expected to increase to 2.1 billion by 2020.

Though presbyopia is a normal change in our eyes as we age, it often is a significant and emotional event because it's a sign of aging that's impossible to ignore and difficult to hide.

Presbyopia Symptoms And Signs

When you become presbyopic, you either have to hold your smartphone and other objects and reading material (books, magazines, menus, labels, etc.) farther from your eyes to see them more clearly. Unfortunately, when you move things farther from your eyes they get smaller in size, so this is only a temporary and partially successful solution to presbyopia.

Also, even if you can still see pretty well up close, presbyopia can cause headaches, eye strain and visual fatigue that makes reading and other near vision tasks less comfortable and more tiring.

What Causes Presbyopia?

Presbyopia is caused by an age-related process. This differs from astigmatism, nearsightedness and farsightedness, which are related to the shape of the eyeball and are caused by genetic and environmental factors. Presbyopia generally is believed to stem from a gradual thickening and loss of flexibility of the natural lens inside your eye.

These age-related changes occur within the proteins in the lens, making the lens harder and less elastic over time. Age-related changes also take place in the muscle fibers surrounding the lens. With less elasticity, the eye has a harder time focusing up close. Other, less popular theories exist as well.

Presbyopia Treatment: Eyeglasses

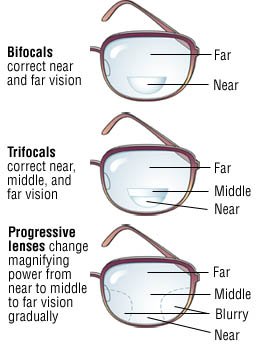

Eyeglasses with progressive lenses are the most popular solution for presbyopia for most people over age 40. These line-free multifocal lenses restore clear near vision and provide excellent vision at all distances, regardless of what refractive errors you may have in addition to presbyopia.

Another option is eyeglasses with bifocal lenses. But bifocals are much less popular these days because they provide a more limited range of vision for many presbyopes. Also, most people don't want to show their age by wearing eyeglasses that have a visible bifocal line.

Also, it's common for people with presbyopia to notice they are becoming more sensitive to light and glare due to aging changes in their eyes. Photochromic lenses, which darken automatically in sunlight, are a good choice for this reason. They are available in all lens designs, including progressive lenses and bifocals.

Reading glasses are another choice. Unlike bifocals and progressive lenses, which most people wear all day, reading glasses are worn only when needed to see close objects and small print more clearly.

If you wear contact lenses, your eye doctor can prescribe reading glasses that you wear while your contacts are in. You may purchase readers over-the-counter at a retail store, or you can get higher-quality versions prescribed by your eye doctor.

Regardless which type of eyeglasses you choose to correct presbyopia, definitely consider lenses that include anti-reflective coating. AR coating eliminates reflections that can be distracting and cause eye strain. It also helps reduce glare and increase visual clarity for night driving.

Presbyopia Treatment: Contact Lenses

Presbyopes also can opt for multifocal contact lenses, available in gas permeable or soft lens materials. Another type of contact lens correction for presbyopia is monovision, in which one eye wears a distance prescription, and the other wears a prescription for near vision. The brain learns to favor one eye or the other for different tasks. But while some people are delighted with this solution, others complain of reduced visual acuity and some loss of depth perception with monovision.

Because the human lens continues to change as you grow older, your presbyopic prescription will need to be increased over time as well. You can expect your eye care practitioner to prescribe a stronger correction for near work as you need it.

Presbyopia Treatment: Surgery

Don't want to wear eyeglasses or contact lenses for presbyopia? A number of surgical options to treat presbyopia are available as well.

One presbyopia correction procedure that's gaining popularity is implantation of a corneal inlay. Typically implanted in the cornea of the eye that's not your dominant eye, a corneal inlay increases depth of focus of the treated eye and reduces the need for reading glasses without significantly affecting the quality of your distance vision.

FDA-approved corneal inlays for presbyopia correction surgery include the Kamra inlay (AcuFocus) and the Raindrop Near Vision Inlay (ReVision Optics).

Presbyopia is an unavoidable age-related condition that causes near vision problems in people aged 40 and over. The gradual loss of vision can interfere with simple everyday tasks like reading, operating a smartphone or tablet, or working on a computer. The good news is that presbyopia can be easily diagnosed through a routine eye exam, and there are a number of treatment options available to help restore near vision.

Check out these seven common treatments for presbyopia

1. Eyeglasses

By far the most common (and simplest) treatment for presbyopia is bifocal or progressive lens eyeglasses.

A bifocal lens is split into two sections. The larger, primary section corrects for distance vision, while the smaller, secondary section allows you to see up close.

Progressive lenses function in a similar manner, except that the sections of the lens optimized for distance and near vision are more blended (as opposed to the two distinct zones that characterize bifocals).

Although a simple and cheap option for correction, there can be associated hassles and aesthetic concerns with eyeglasses, which is why some people opt for an alternative solution such as contact lenses or surgery.

2. Contact Lenses

Multifocal and monovision contact lenses are very common treatments for presbyopia.

Multifocal contact lenses function in a manner similar to bifocal eyeglasses and are designed to provide clear vision across various focal points. Patients can work with their eye doctor to find the best fit, whether a soft lens, a rigid gas permeable lens, or a hybrid. They also have the added bonus of being available as disposable lenses.

Monovision contact lenses offer different prescriptions for each eye; one for distance vision and one for near vision. This can be problematic for some people who have a difficult time making the adjustment. Visual acuity and depth perception can be affected.

Both eyeglasses and contact lenses are temporary solutions for presbyopia that require ongoing maintenance. These days more people are opting for a permanent treatment through corrective

surgery.

3. Monovision LASIK

Although LASIK cannot treat the root cause of presbyopia, there are LASIK variations that can help reduce your need for reading glasses or bifocals.

Monovision LASIK is a procedure that corrects the dominant eye for distance vision while leaving the less-dominant eye nearsighted. Why? Because a mildly nearsighted eye is able to see things up close without reading glasses. The only problem is that distance vision with monovision LASIK is often not as crisp as it would be without the nearsightedness. Many people find this to be an acceptable tradeoff for improved near vision and, as such, Monovision LASIK is the most widely

used surgical correction for presbyopia.

4. Multifocal LASIK

Whereas monovision LASIK improves distance vision in one eye and near vision in the other, multifocal LASIK (also called PresbyLASIK) creates multiple “power zones” across the surface of the cornea to improve the depth of clear vision focus at any distance.

Multifocal LASIK is not yet approved by the FDA, though it is progressing through the clinical trial process and has been approved in several other countries.

5. Corneal Inlays

Corneal inlays are tiny implantable lenses that are surgically placed in the cornea to improve vision affected by presbyopia. There are currently two FDA-approved corneal inlays available, each of which works in a slightly different fashion.

The KAMRA corneal inlay is implanted in the non-dominant eye where its pinhole design allows it to extend the patient’s range of vision from near to far.

The Raindrop Near Vision Inlay is a biocompatible hydrogel that is designed to closely resemble the human cornea. The Raindrop Inlay treats presbyopia in a manner similar to multifocal contact lenses

by changing the curvature of the eye.

6. Conductive Keratoplasty

Also called NearVision CK, conductive keratoplasty incorporates the use of a handheld probe that sends radio waves to targeted spots on the cornea to adjust its shape. It is most often performed on only one eye, making it a form of monovision correction.

In addition to being used as a treatment for presbyopia, conductive keratoplasty has been studied as a treatment for other eye conditions including keratoconus and astigmatism.

7. Refractive Lens Exchange

Refractive lens exchange (RLE) is an invasive procedure that involves replacing the natural lens of the eye with an artificial alternative. RLE treatment for presbyopia is similar to that used for cataract surgery. An artificial intraocular lens (IOL) replacement can improve near vision and reduce a person’s dependence on reading glasses. The surgeon performing RLE can utilize a monovision strategy with a distance-correcting lens in one eye and a near-correcting lens in the other, or a multifocal strategy where the lenses provide vision correction across a range of distances.

The best solution for each patient depends on age, current status of distance vision, and personal preference. Consult your eye doctor to determine which of these seven treatments is best for you.

Remember to subscribe to our blog before leaving.